EURO 1984

Euro 1984. The tournament where France’s Michel Platini firmly established himself as one of the world’s finest footballers in front of his home crowd, where 19-year-old Michael Laudrup made his bow on the big stage, and where England didn’t even qualify – leading to both BBC and ITV refusing to broadcast the tournament.

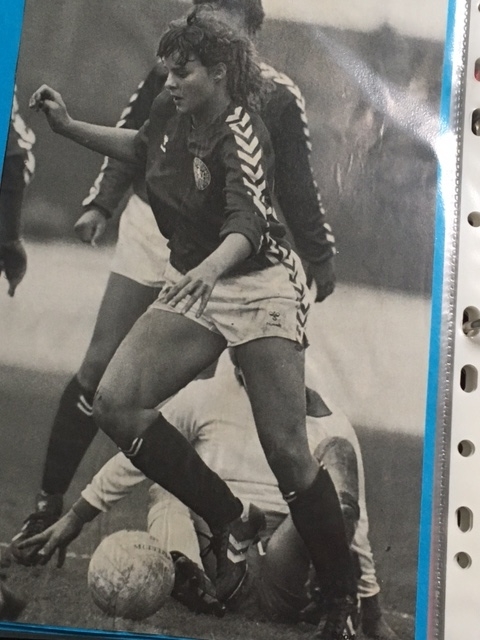

But there were two Euro 1984’s, preceding the main event by a couple of months was the first ever European Championships for the women’s game to run under the UEFA name. It wasn’t entirely official, only 16 teams took part in qualifying meaning it couldn’t be completely classed as an official tournament, games were 35 minutes a half and size four footballs were used, but it was the first European tournament not to have the word ‘Unofficial’ in the title.

To qualify, teams faced a mini group with three other countries, usually their local neighbours, for a spot in the tournament. There was no host, two legged semi-finals and a two-legged final would be played home and away rather than at neutral venues, but it kicked off a new era for women’s football and the tournament played host to some of the finest footballers to ever grace the game.

The four teams who made it were Sweden, Denmark, Italy and the late Martin Reagan’s England. Sweden had dominated Scandinavian rivals Norway, Finland and Iceland in qualifying, conceding just one goal in six qualifiers.

England also went through with maximum points and the same goals against tally after seeing off Scotland, Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland, whilst Italy brushed aside France, Switzerland and Portugal. And yes, you guessed it, they conceded just one goal.

Denmark had it tougher, they conceded five and scored only eight, but it was enough for Flemming Schultz’s side to finish ahead of Netherlands, Belgium and West Germany.

Despite just four teams participating, the tournament would be stretched over almost two months, the first matches played on April 8th.

Martin Reagan’s England side hosted Denmark in front of just a thousand people at Gresty Road, whilst 5,000 would turn up in Rome to watch Italy face Sweden.

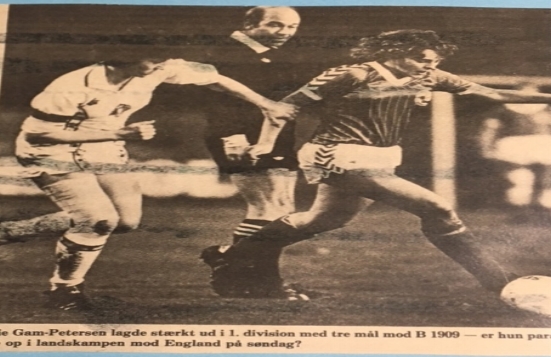

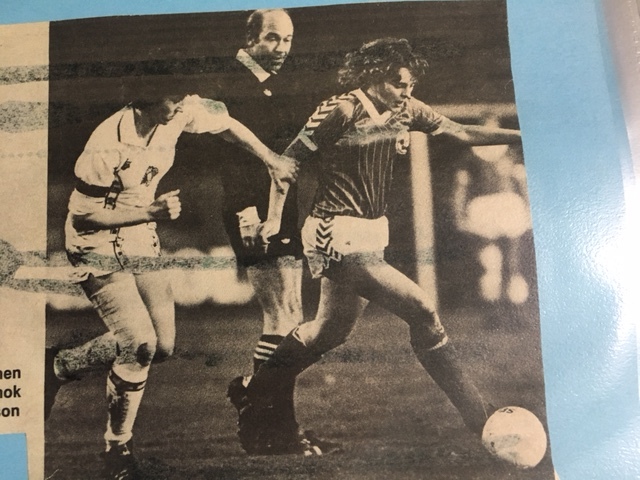

But the tournament nearly didn’t happen at all, Denmark’s Annie Gam-Pedersen was only 18 at the time and recalls that the teams had to agree to FIFA’s rulings.

“In FIFA, there were old men and what we learned was that to let this tournament go ahead and let the women play, they wanted that we only played 35 minutes each half and played with a smaller ball, a size four ball.”

Pedersen adds, “The Scandinavian teams at that time were playing 45 minutes like the men, so it was a challenge for us to change and to also play with a smaller ball. But that was the deal for FIFA to let us play this tournament, it was quite difficult.”

They weren’t the only stipulations FIFA imposed, for the qualifying rounds, they insisted on something which would cause plenty of controversy in the modern day game.

“They also said referees for the qualifiers would be from the host organisation,” says Pedersen. “So in Denmark, we would have a Danish referee but when we went to Holland and Belgium and West Germany we would have their referee – I don’t think that would happen today!”

England captain at the time was tenacious midfielder Carol Thomas, her ‘no nonsense’ style and fantastic tackling ability would lead to England’s goal in the final against Sweden, but the journey started long before that for Thomas.

“According to one website, at the time Denmark were ‘World Champions’ based on having beaten the previous holders of that position,” Thomas recalls.

“We played well in both games, the two victories seemed reasonable and it was job done. Perhaps we should have celebrated more, as we were now deemed unofficial ‘World Champions’.

For Denmark, the outcome was a disappointment, and whilst Pedersen admits her team played “awful”, their preparation wasn’t exactly what you would describe as ideal.

“I played in both games against England,” she recalls. “We lost 2-1 in Crewe but the English were not organised. When we arrived, they hadn’t organised anywhere we could practice and we had to transport ourselves to training.

“We only got 30 minutes to train at Manchester City, it wasn’t very good but nobody heard about because nobody cared. We were sure we’d beat them but we played even worse in the second game, we weren’t used to these games. In our national league, maybe two games a year were competitive and the rest were won in a convincing way.”

Pedersen adds that Denmark were ahead of their rivals when it came to organisation surrounding the women’s game, and it wasn’t just England playing catch up.

“I think in Denmark we’ve always been quite organised,” she says. “When we played West Germany, we beat them both times and they had an excuse that they got no attention at all. I think our first game against them was the first time people could bet on a women’s football match.

“Then the first time we played Belgium was the first time they showed a national women’s game live on Danish TV. You could say it was a turning point for Danish women’s football because it was more attention than we’d ever had.

Meanwhile, over in Rome at the Stadio Flaminio, a thriller was being played out between Italy and Sweden. Both possessed two of the deadliest strikers in football at the time, Carolina Morace for the hosts and Pia Sundhage for the visiting Swedes.

Both would score in both legs, and Morace recalls the disappointment on just missing out on the final.

“We were disappointed, of course,” says the former striker. “But the number of players involved in women’s football in Sweden was much greater than that in Italy.

“So we tried, we were disappointed because of course, you want to win these important games, but at the time it was just a dream to be involved.

After a 3-2 defeat at home, the Italians went to Linkoping for the second leg with a reasonable chance of turning the tie around.

Morace and Sundhage would once again be the stars, but with the game played at the end of April, Morace recalls one quirk of the match that was fairly new to their team.

“Obviously we lost and that meant we were out,” she recalls. “But we played a match just between ourselves and we played it at 4 am one morning. In Sweden, it is light all day and light all night, so it was strange for us to get used to!”

Whilst other players have kept memories of the tournament to look back on, Morace can barely remember either of her goals and admits she hasn’t kept hold of too many things from the tournament.

“I don’t remember the goal at all,” she laughs. “I don’t really keep things; my job was just to help the team. The only thing I have in my house is a Hall of Fame trophy I was given two or three years ago. I have more things back in my garage in Rome but I’m not the kind of person to look back, I prefer to look towards the future, that’s just my personality.”

Like her foreign colleagues, Morace was left slightly bemused by the decision to change the rules to accommodate the first UEFA tournament for women.

“It was a bad rule because football is a football. If the game is 45 minutes a half, why do we have to play 35 minutes?”

Morace adds, “But it wasn’t difficult, you can train and adapt so we just had to get on with it.”

Along with Sundhage, Morace was one of Europe’s most talented centre forwards of the time. She would end her international career with an incredible 105 goals in just 150 appearances, including four goals at the first FIFA World Cup in 1991 – three of them forming a hat-trick.

Morace scored over 500 goals in the Italian league and even served up a treat at Wembley one warm August afternoon. Before the 1990 Charity Shield between Manchester United and Liverpool, Morace’s Italy played a warm up game against England, still under the guidance of Reagan, beating the hosts 4-1. Morace scored all four, but oddly she has a rather plain view on her talents as a goal scorer.

“In my opinion, I was just a normal player,” she says. “I never felt I was better than other players, my role was to score goals, that’s it.

“It wasn’t that I was better than my team mates. The goalkeeper has to save, the defenders have to stop goals, the midfielders have to pass and I have to score, my role was just normal.”

Like others, Morace noticed a brief difference in media attention when Italy were involved in Euro 1984, but the excitement wouldn’t last.

“We did get more attention from the media,” she recalls. “Our country has never been so good for women’s football, but we became a little more well known, people started to follow us.

“But nothing has really changed from that time to this…”

It would be almost a month before Sweden and England reconvened in Gothenburg for the first leg of the final.

To be played at the famous Ullevi, where a year before Aberdeen had famously defeated Real Madrid, a crowd of just over 5,000 settled down to watch Sweden take the first leg by a margin of 1-0 against Reagan’s side – you can even enjoy the match in full on YouTube.

It was Sundhage who was once again the hero, but it was also a special moment for young 21-year-old Lena Videkull.

Videkull would go on to become one of the best strikers in Sweden’s history, but at the time it was her very first appearance for her country. No friendly matches, and no previous experience in the tournament, Videkull was chosen to start on the biggest stage.

“It was my first game ever for the national team,” recalls Videkull. “It was very big for me to play with Pia Sundhage and Anette Borjesson.

“Those players were very, very good and I was extremely nervous. I have one memory from when I met everyone at the hotel, I was so nervous I drove my car around the parking lot one more time before I went in because I was just so nervous to meet all these famous players.”

Videkull may have been a rookie, but over the course of time she would become one of the most famous names in Swedish women’s football. She is the third top scorer in the nation’s history, behind only Lotta Schelin and Hanna Ljungberg and level on 71 with the great Sundhage.

But in 1984, Videkull was the new kid on the block and determined to make an impact when the teams walked out at Ullevi.

“I wanted to start, I wasn’t satisfied to be on the bench,” she says. “I think there were about 5,000 people there which was a lot for women’s football. I had scored a lot of goals for my club, there were some injuries and I got my chance.

She adds, “I think I took it because I stayed with the national team until 1997!

“I almost scored [Videkull hit the post in the 18th minute] but I got the highest score in the player ratings after the match. It was from 1 to 5 and my first game I got 5. I was satisfied with that.”

For England’s Thomas, she has fond memories of a goal line clearance that kept her side in the tie going into the second leg, but accepts for England it was a “backs to the wall performance”.

“Sweden were considered to be the best team in the world alongside Italy,” she recalls. “I remember it was a very sunny day with a large crowd. For much of the game we were having to defend, the Swedes played good, attacking football at pace.

“My most treasured memory of that game was my left footed goal line clearance. I would like to think that kept us in the tie and inspired us to keep to the task. We were defeated but not down, I felt that going into the second leg only 1-0 down gave us a real chance of winning.

But conditions in the second leg were less than perfect, as both players recall the day the tournament was decided.

“Then we came to Luton for the second game, the practice in Sweden was perfect but I think it’s fair to say it was a little bit different there,” recalls Videkull.

Yes, that’s right, Luton Town’s Kenilworth Road hosted a major European final, Wembley was apparently out of the question for the women’s team. The main clubs in the capital had no interest in hosting the showpiece occasion, so Kenilworth Road it was.

“The conditions couldn’t have been more different,” says Thomas. “We adapted quicker and better but it was resembling something like the ‘Somme’. Again, I have the memory of making two block busting tackles, first to win the ball and secondly to ride a tackle from an opponent, that let me slide the ball to Linda Curl who scored a fabulous goal from out wide on the right.”

Footage of the decisive second leg is practically non-existent, but SVT did produce a documentary, the third part of which contains video clips of Linda Curl’s goal, the penalty shootout that followed and an emotional reunion between Kenilworth Road and Sweden’s manager at the time, Ulf Lyfors. It also gives a very good visual description of how bad the pitch was, if you can call it a pitch.

Heavy rain before the match meant the pitch was a mud bath and almost impossible to play on. Today the game would likely have been called off, but there was no such option for Videkull and her team mates.

“I don’t know what you’d call it but we didn’t train on a football pitch, it was almost like a park.

“I didn’t play the whole game and I’m happy I didn’t end up taking a penalty,” she laughs. “It wasn’t grass we were playing on, it had been raining a lot and it was so difficult to play on.”

Videkull adds, “If it was today it would have never have been allowed to go ahead, but in that time we had to play. Luton had taken away the grass and replaced it was grass which wasn’t natural. The centre circle was just mud, we all just ran around!

“I think the English loved it because they were very good at the long balls, so it wasn’t a surprise they won that game. But we were better team on penalties and we had one of the best goalkeepers in the world [Elisabeth Leidinge].

The game wasn’t shown in the UK, just a couple of reporters from England were in attendance whilst Sweden brought over a strong media group to cover what would be a historic occasion.

“Credit to the Swedes, they dug in and battled on,” says Thomas. “When the final whistle blew I was so pleased we had won the game but I knew that with the poor conditions it wasn’t over yet.”

Curl’s strike after half an hour ensured that after two matches, the first European Championships would be decided on penalties.

Curl herself missed, but fortunately so did Helen Johansson for the Swedes. Defender Lorraine Hanson missed too for England, so Sweden only had to score their final penalty to seal the deal. Obviously, duty of winning it would be left to Sweden’s star, Pia Sundhage.

“Pia took the last one,” recalls Videkull. “You could feel she wasn’t going to miss because she was a strong player, thankfully she didn’t.”

For Thomas, the memories are quite different, “Sadly, we all know what happened. The confidence of our players seemed to go as the Swedes struck the ball so much better than us. I lifted the runner up shield with pride because, to this day, I know I captained a great England squad of players.

Morag Pearce, England’s left back, played the whole match but didn’t take a penalty, yet she clearly remembers the pain of Sundhage scuffing the ball into the bottom corner.

“It was the worst feeling ever,” says Pearce. “Sick to the stomach comes to mind, it’s an awful feeling you just can’t describe.

“I recall the muddy pitch, which seemed to suit us, we had chances but unfortunately we didn’t take advantage of the conditions.”

So, what of the attention surrounding the tournament? With the men’s Euro’s soon around the corner, all eyes were on France and who would win out in a competition which had been established long before the women’s equivalent came along.

Denmark’s Pedersen recalls that it was the first time there was any attention around the women’s team going into the tournament.

“When we qualified, the semi-finals got some attention,” she says. “We were invited to a party with the Denmark footballers, that was the first time we ever appeared there. The media did pay attention and they did show it on TV too.

“But it was a different situation, we weren’t all together all the time. Today you’d go to the Netherlands and you stay there for a month. For us, you play the games home and away and that was it.”

Carol Thomas though was left disappointed by the lack of national television coverage in England, but there was a rare opportunity post-tournament for the captain to spread the word that the women’s game was growing.

“Sadly, none of the TV networks took up the recording and it was never televised in full,” she remembers. “The following morning after the final, I became the first women footballer in this country to be interviewed on national TV by Selina Scott and Frank Bough on BBC’s Breakfast Show.

“It’s unfortunate that the impetus the women’s game that had started that month was not taken up by the FA. Just think where the women’s game may have been in all the intervening years if they had.

But Thomas will always be thankful for the fans that came out in horrendous conditions to support their country.

“Despite the weather, the fans that did out that day were great and despite the numbers, Kenilworth Road seemed full. It was a good crowd for that era, but on reflection, it was a real shame that one of the big clubs did not make their grounds, or dare I say it, Wembley available for the day.”

For Sweden, they possibly got more attention than any of the teams involved in Euro 1984, and Videkull recalls the first time people were “really looking at the women’s game,” as she describes it.

“There was a lot of media attention in Ullevi but in Luton it wasn’t really the same,” she remembers. “But we won and that’s it. Before the game, people came and watched our training and reporters came to watch too, it was different to what we were used to.”

The attention, in particular, was special for the 21-year-old, not only was she embarking on her first of 111 games for the national team, she was doing it for a team from a town of less than 50,000 people.

Whilst key stars like captain Borjesson, Sundhage and Leidinge played for the then mighty Jitex BK, Videkull played for Trollhattans IF, and the 80s were the peak years for her side.

“It was good for someone from where I was playing to win the European Championships,” she says. “There was never really anything about women’s football in the newspaper but I think everyone was happy to have someone from Trollhattans become a champion.”

And what of Sundhage? Whilst the pair would end their playing careers on equal footing, Sundhage has just stepped down after coaching her home nation for five years, whilst she won two Olympic gold medals and reached the 2011 Women’s World Cup final whilst coaching the USA.

Better known to the younger fan as a legendary manager, Videkull says she was much more than that.

“She was very, very good, she was one of the best in the world,” says the former striker. “Even now, comparing her to people like Mia Hamm and the new players now, she’s one of the best.

“She was so special, she could head the ball, could play with her left foot, her right foot. She was strong and just something very special – one of the best in the world.”

Sundhage herself has fond memories of the first European Championships…

“It was a long time ago,” says the Swedish legend. “It was a gold medal for us and penalties are always interesting!

“Of course, I have fond memories, my players today weren’t even born when we won the gold medal,” she laughs. “It was special for me, of course, back in the good old days…”

The final word rests with captain Thomas, who still recalls what she said in an interview immediately after the match, a point that somewhat resonates even in the present day.

She adds, “I was asked about the match by a freelance TV company who had recorded the game. My response, somewhat bluntly was, “If people don’t come to watch women’s football after that, then there is something wrong with them!” You can take the girl out of Yorkshire, but you can’t take Yorkshire out of the girl…”

By Rich Laverty, IBWM Senior Writer. Rich would like to offer a personal thank you to the legends of the game who all agreed to speak exclusively about their memories of Euro 1984, and a thank you to Women’s Football Archives for providing so much useful background information for the feature.

Thank you to Annie for providing personal newspaper cuttings from the tournament and to Morag for scans of the final matchday programme.

Pia Sundhage is now 57 years old and has just stepped down from her position as the head coach of the Sweden national team.

Lena Videkull is now 54 years old and is working in Sweden for Damallsvenskan club FC Rosengard.

Annie Gam-Pedersen is now 52 years old and working at the University of Southern Denmark.

Carolina Morace is now 53 years old and the head coach of Trinidad and Tobago’s women’s national team.

Morag Pearce is now 59 years old and a teaching assistant in Southampton.

Carol Thomas is now 62 years old and retired from working in football in 2009. She now spends her time trekking around the world and scaled the Andes and the Himalayas.