THE LEGEND OF THE LONE WOLF

Ask any English football fan of the late 1940's and 1950's how they would describe Jimmy Hagan and you will probably be told he was the complete Inside Forward, that his body swerves and footwork could leave the best defenders stranded and that his one England cap was a travesty. Fellow professionals of the time have spoken about Hagan in similar terms. Ask any Benfica supporter of a certain vintage and they will describe a man of principle, of strong work ethic and a leader by example. A leader who took the Lisbon side on a magnificent run of success in the early 70's and earned the respect and lasting friendship of the great Portuguese player of that time; Eusebio.

The son of Newcastle United, Cardiff City and Tranmere Rovers footballer Alfie Hagan, Jimmy was born in Washington, County Durham in 1918. It was a tough upbringing in the mining community and, with his father having moved away from the family to further his football career, Jimmy became the man of the household; assuming a level of maturity and a principled stance that was to cause as many ructions as it would bring successes in his life. In many ways he was like his father and that meant when they were together they often clashed. As stubborn and self-confident as each other, Jimmy was to adopt the strong disciplinarian principles of his father, but without the violence and abrasiveness that, sadly, Alfie brought with it. Over time his relationship with his father became increasingly difficult. As Jimmy demonstrated his tremendous gift for the game, progressing to England Schoolboys, it was increasingly apparent that he was going to be a much better footballer than his father; something that Hagan senior struggled to come to terms with. At one point Alfie destroyed all the photos of his son's schoolboy career, another time he killed Jimmy's favourite racing pigeon. These incidents contributed to Jimmy's quiet but hardened demeanour; a protective shell from the world.

At 15, he was approached by Derby County and taken on by George Jobey, a former teammate of his father at Newcastle. Over the next five years his playing time was limited. As good a player as he was, there were more experienced and talented inside forwards ahead of him in the pecking order. When he did get an opportunity, he demonstrated enough to interest Sheffield United manager Teddy Davidson. Joining the Blades in 1938, Jimmy's early years at Sheffield United were interrupted by the War. After making an instant impression on United fans he was enlisted into the Army Physical Training Corp in Aldershot and went on to frequently guest in a strong Aldershot FC side whilst making a few appearances for United each season.

His time at Aldershot in representative games for the Army accelerated his progression to the England side, albeit in unofficial wartime internationals. Alongside his many certificates for Wartime internationals, Jimmy gained one full cap, against Denmark in 1948. It is fair to say his hopes of international recognition were hampered by some of the legendary players sharing his position at the time; Len Shackleton, Raich Carter and Wilf Mannion. Towards the end of the war, Hagan spent some time in Germany and was part of the Army contingent who liberated the Belsen-Bergen camp, a special, but emotionally difficult task. Whilst in Germany he kept playing football, including games for the Army against Schalke 04 and others. It was 1946 before he was demobbed back to Sheffield.

Over the next twelve years Hagan was the figurehead of a Sheffield United side that won nothing of note, but provided many great footballing moments. Opponents and press talked of a man who could just pluck a passing ball out of mid-air, before mesmerising defenders with speed of mind, speed of thought and superb control. He was a goal maker and a goal taker and when people spoke of Sheffield United the reality was that they were most probably talking of Hagan.

His time at United came to an end at the age of 39. The board of directors, noting his lack of pace, decided he was no longer suitable for selection for first or second team fixtures. Interestingly the board also noted that he shouldn’t be considered for a coaching role because he wouldn’t be able to impart his knowledge to the players; judgement that was to prove hugely misguided and may well have been to the club's detriment.

After time spent playing for All-Star representative teams, Hagan was offered is first managerial opportunity at Peterborough, yet to be elected to the Football League and playing in the Midlands League. He took them to two successive Midlands League titles and at the end of the second title winning season they won election to the Football League. In the first season in the League Hagan led them to the top of the Fourth Division, setting league records for points and goals; the latter an amazing 134. His time at Posh came to a close following a change of chairman and interference from above. Following the ructions, Hagan was asked to resign. He refused and so was sacked.

In his next managerial position, at First Division West Bromwich Albion, he quickly developed a reputation for leading by example. Now in his late 40's, he was still training every day and had an amazing level of physical fitness. Hagan never drank alcohol or smoked, but never let it stop him enjoying himself with those who did. Alongside his supreme levels of athleticism, the football skills had barely dimmed. Hagan changed thinking in terms of player preparation, but at the same time wouldn’t set the players a task or exercise that he couldn’t complete himself. Training sessions were reduced from the standard two hours to ninety minutes, but with a greater intensity than the players were used to. With the changes and the strict approach he applied, relationships between players and manager became fractious and came to a head in December 1963. Hagan demanded that his players trained in shorts and the players, led by Captain Don Howe, refused. A standoff ensued which led to the players refusing to train with Hagan left conducting the sessions in shorts, with reserve team players. The "strike" was eventually brought to a close when the directors negotiated a compromise by which the players would switch to shorts after 15 minutes of the session. In later years, perhaps recognising elements of Hagan's strong disciplinarian approach in his coaching style, Howe acknowledged he had been wrong and that he should have acceded to the manager's request.

Despite the friction, Hagan yet again brought success to the club he was managing; reviving a struggling side and winning the League Cup in 1966 alongside a sixth place finish in the League. The following season was more of a struggle; early exit from European competition was followed by a League Cup final defeat at Wembley and Albion were battling against relegation. Hagan was relieved of his duties at the end of the season. There followed three years out of management; compensation from Albion funding a driving school business, whilst he kept his football interest with coaching for the FA at Lilleshall and acting as a member of the Pools’ Panel, all before Benfica came calling.

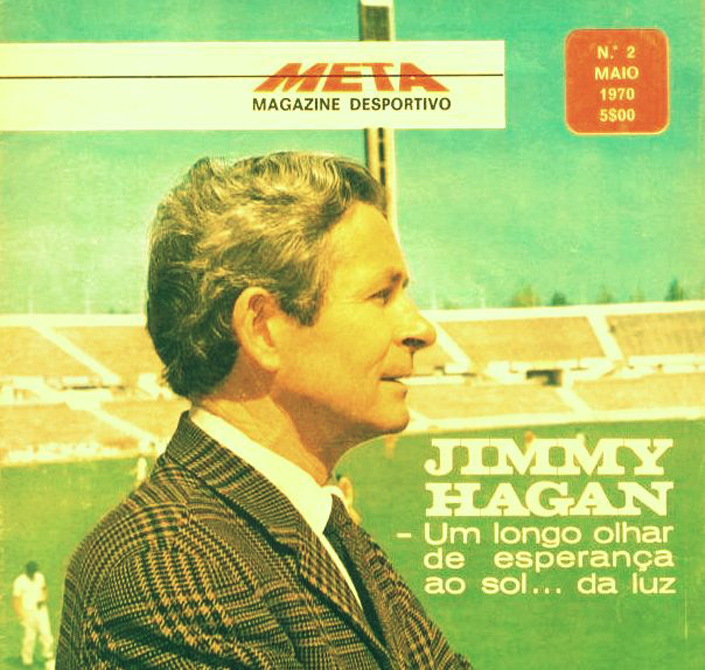

It was late in the 1969/70 season and the Aguias, European Cup finalists just two years previous, were slipping. Eusebio remained the hub and central figure of the side, but complacency had slipped in and the players were just not working hard enough. It was felt that an English manger would arrest this slide and up the work-rate to the level required. It was Bogota Bandit Charlie Mitten, who had connections in Portugal, that recommended Hagan to the Benfica directors, who had reportedly approached, and been turned down by Alf Ramsey. It was a seemingly odd move; Hagan had been out of management and not wanted by clubs at home for three years. On top of that, this opportunity was taking him out of his comfort zone and putting him in a new country and culture. It also put him on a deal comprising just a basic salary, leaving him to find a home and buy a car. Hardly a financial incentive. What he did stipulate in return was that his contract terms afforded him full control of on-pitch matters and team selection; his experience at Peterborough and West Brom re-emphasising how important this point of principle was.

Despite now being in his 50's he led the team's training sessions. Recognising that stamina issues were a key element to be addressed, he set a punishing schedule including an exercise of running up and down the steps of the Estádio da Luz. Eusebio later said that Hagan's training regime was considered harsh by many of his team-mates, with some physically sick from their exertions. His training worked though; the players were not lacking in skill or technique, but the physical requirements of playing for ninety minutes and more had previously proved beyond them. The team's results started to improve as the players lasted longer in games and held on to results they would have previously surrendered.

As at his other clubs, Hagan would never set his players tasks that he couldn't do himself and was always able to demonstrate his requirements. One of his favourites, a party trick as such, was the crossbar challenge. This involved hitting the crossbar with a ball from the edge of the penalty box. One day Hagan set the challenge at the end of a session and expertly demonstrated how to do it. Having subsequently showered, changed and had lunch, he returned to find some of the players still there trying to do match his trick.

Benfica eventually finished second in the 1969/70 season, some eight points behind Sporting, but over the following three seasons Hagan brought huge success to the club. Three league titles were claimed in three seasons, with the League and Cup double achieved in 1971/72 Benfica were also finalists in the cup in 1971. The Águias became the first Portuguese club to go an entire season unbeaten, winning 28 of their 30 league games in 1972/73 and scoring 101 goals in the process. Of those 101 goals 43 were scored by Eusebio. Now coming to the end of his career and playing in a deeper role in midfield, Eusebio won the European Golden Boot award with Hagan continuing to bring the best out of The Black Pearl. Away from domestic football, they lost their 1972 European Cup Semi Final 1-0 to eventual winners Ajax, and lost to Derby County in the second round the following year.

The unassuming manager was frequently mobbed by fans in the street and afforded the level of recognition far beyond what he had received in England, but still wasn't comfortable with. The demands of the Portuguese press were something new to him as well. His discomfort with their sniping, alongside his quiet manner left Hagan with a reputation for being uncommunicative and un-co-operative; often referred to as "The Lone Wolf" or "Mister No Comment" by journalists. Not that they could take that criticism any further, his team's results and success saw to that. His success led to an extended tenure rarely achieved at the club in those times. Five of his six predecessors lasted less than one year, the sixth lasting two years. The three managers that followed lasted a year. When the end came at Benfica for Hagan, it wasn't due to failure on the pitch or fault with his management, but down to an issue of principle that could be traced back to those original contract negotiations.

In September 1973, Benfica afforded Eusebio a benefit match with international players flying in to take part. Hagan demanded the same level of preparation from the Benfica players as he would for any other game. Whilst Eusebio and others complied; Diamantino and Portuguese internationals Toni and Humberto did not. Having warned them that they wouldn't be selected if they didn't make the effort, Hagan went through with his threat. Pre-match and word of the situation had reached club president Jorges Coutinho, who summoned Hagan and told him to select the three players. Hagan refused, but what he didn't know was that Countinho had secretly told the players that they would still play. When Hagan walked out on to the Estadio da Luz pitch pre-match, he saw the three rebelling players warning up. Recognising that his one contractual request had been broken and, despite the importance of the occasion, he walked out of the stadium never to return. It took an emotional Eusebio, arriving on Hagan's doorstep after the match, to persuade the stubborn coach to attend the celebratory dinner that evening. The mutual respect between great player and great coach enabling the result that, deep down, both wanted.

Whilst his contractual wrangling with Benfica was being sorted, Hagan worked for free at Estoril Praia, taking them to the Third Division title and then, with political instability in Portugal, Hagan headed to the Far East, spending two years coaching Al Arabi of Kuwait. Despite his success at Benfica, no British clubs called and when his Kuwaiti contract expired in 1976, Jimmy returned to Portugal, coaching five different clubs over the next six years.

His return was controversial, taking over at Benfica's city rivals Sporting Lisbon. He took them to second in the league, behind Benfica, and to the semi-finals of the Portuguese Cup. The following season he joined Boavista, where Jimmy took Oporto's second club to Cup success. Spells at Vitoria Setubal, Belenenses and finally back to Estoril followed, before Hagan stepped away from the professional game aged 64. He remained involved in football, coaching the expats team in Lisbon, and was to spend several further happy years in Portugal. He remained a humble man, happy to talk about football, life in general and the past, but not about himself.

It was a combination of failing health and the onset of Alzheimer's disease that led to one return to England and, following the death of his wife in 1996, Jimmy spent his final years in a care home in Sheffield, just a couple of miles from Bramall Lane where he demonstrated such magical play. Jimmy Hagan passed away in 1998, just after his eightieth birthday, remembered by football fans in two countries and by those that had played for and alongside him. Such was Eusebio's fondness and friendship with Jimmy, he returned to Bramall Lane several years later to unveil a bronze statue of Hagan saying; "Jimmy is still in my heart to this day….. he was a good player, a wonderful manager and a great man".

Follow Ian on Twitter @Unitedite.